Note: This post includes segments that were excluded from the podcast episode.

After many long months of anticipation, the Art Institute of Chicago recently unveiled the new Mary and Michael Jaharis Galleries of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Art (on November 11, 2012).

The new installation has quadrupled in size and, with its fresh redesign, encompasses the entire circuit overlooking the Art Institute’s open-air McKinlock Court (galleries 150-154). The long corridors of the new Jaharis Galleries lined with Classical treasures amidst bustling visitors almost give me the feeling of hobnobbing among the philosophers of an ancient Athenian stoa.

Ironically, with the increased space dedicated to Greek, Roman, and Byzantine art, the Art Institute’s collection is not substantial enough to fill it. Over a quarter of the approximately 550 works of art on display are on loan from various private collections and other museums, including the Oriental Institute and Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the Getty. [1]

The Jaharis Galleries are designed in part by Kulapat Yantrasast of wHY Architecture, although I’m not exactly sure which part, as this design is a radical departure from Yantrasast’s earlier commission in the Art Institute, the Roger and Pamela Weston Wing of Japanese Art, featured in episode 34 of the Ancient Art Podcast, Haniwa Horse and Hokusai’s Ghosts. The refined simplicity and pedestrian-friendly layout of the Weston Wing seems to have gotten lost in translation from Japanese to Greek and Latin. The congested atmosphere of display cases in the Jaharis Galleries proves a little troublesome for groups larger than what I can count on my hands (I presently have all my fingers). You might find yourself careening into fellow visitors like a sailor dashed upon the Peloponnesian crags, lured by the sirenic call of some Athenian vase or Antonine portrait bust.

The galleries begin with two works that form a bridge to other collections in the museum, which broadly express inspirations for or from the art of Classical antiquity. The c. 3000 BC Mesopotamian Statuette of a Striding Figure on loan to the Art Institute reminds us that Classical Civilization had one foot firmly placed in the cultural heritage of the Ancient Near East and Egypt (aka “Oriental”), which we have explored repeatedly in the Ancient Art Podcast. [2]

The Art Institute’s refreshingly modern Cycladic Female Figurine from c. 2500 BC tantalizes visitors emerging from the museum’s Modern Wing with a simplified elegance and abstraction tantamount to Pablo Picasso. This reminds us of Classical art’s far-reaching fingers in European Modernism and in other areas of the collection, like 19th century American sculpture found in the adjacent Classically-inspired sculpture court [3], and in the Hellenized art of ancient Gandhara seen in the adjacent galleries of Asian art. [4]

Beyond these initial sentinels, the ancient collection is arranged chronologically and culturally. For example, Greek art begins with ceramics of the Mycenaean Bronze Age, takes us through the Geometric, Archaic, and Classical Periods, and concludes with Hellenistic art of the age following Alexander the Great before pleasantly segueing into Etruscan and Roman art.

One benefit of the aforementioned sea of display cases (as in Greek islands dotting the Aegean) is that the works have been relieved of their punitive “time-out” in corners and along the walls. I am especially delighted now to see most objects fully in the round, which had previously teased me for years with only glimpses of their back sides. As a friend and colleague put it: “There are some pretty good derrieres in the ancient galleries!”

Truly spectacular is the brilliance of radiant daylight streaming into the galleries—most notably the Greek gallery. The powerfully raking light beautifully highlights the subtle engravings on the surface of the Greek vessels, used by ancient painters to outline shapes and figures to be filled in with slip and pigment. It may cause something of an initial fright to see powerful sunlight bearing down on vividly colored 2,500 year-old treasures, but take comfort in knowing that the clay-based, fired colors of Ancient Greek ceramics are not particularly sensitive to light. Furthermore, a UV-light filtering film applied to the windows eliminates the more dangerous part of the light spectrum. [5]

Included among the ceramics, sculptures, and jewelry of the Hellenistic Period is a somewhat less than impressive fragmentary stone head of a Ptolemaic Egyptian pharaoh (Anonymous loan, 20.2012). Placed with its back against a large south-facing window, the details of this head can be difficult to discern on a sunny afternoon, but it at least serves as a vehicle for a discussion of Ptolemaic Egypt and an excuse to include one Egyptian piece in the newly expanded galleries.

Conspicuously absent from the Jaharis Galleries, though, is the Art Institute’s beloved collection of Ancient Egyptian art. Gone is the world’s most beautiful Mummy of Paankhenamun. The Statue of Ra-Horakhty has flown the coop. Osiris must have fallen in his own trap door. And that Middle Kingdom ship has sailed. With the ancient art galleries quadrupling in size, one can only wonder how there apparently wasn’t enough room for the Egyptian art. As the Egyptian collection gathers dust in storage, its future location within the Art Institute remains a mystery. Perhaps they could take the initiative and place it among the art of Africa? In the mean time, I’ll derive pleasure in pointing out that the coin display cases throughout the Jaharis Galleries are unabashedly pyramidal in shape.

As you make your way around the corner from Greek to Roman art, it’s tempting to establish a connection between ancient and modern. You waltz among the graceful curves of Hellenistic sculpture and vibrant primitivism of two bronze Sardinian figurines and Etruscan pieces set against the backdrop of the Art Institute’s gallery of public modern art in Chicago. This include maquettes for Alexander Calder’s Flamingo in Federal Plaza, Joan Miro’s variously titled piece [6] at the Cook County Administration Building, Pablo Picasso’s untitled sculpture in Daley Plaza, and the famed America Windows by Marc Chagall. Many of these and other Modern artists looked to antiquity as inspiration for their groundbreaking artistic styles.

Happily, no longer is the collection of ancient glass sequestered in its previous isolation ward, but is now fully integrated and dispersed throughout the Jaharis Galleries, serving to help contextualize the art of glass in the broader narrative of ancient civilization.

A delightful new promised gift to the Art Institute is a collection of eight Roman mosaics related to feasting and merriment. One of my favorites is this charming fish on a platter. The gentle smirk gracing its lips makes me wonder if the fish was not entirely displeased at being served for dinner. Or perhaps this helped a particularly over-empathetic Roman patron overcome his or her vegetarian inclinations. And while mosaic tesserae are generally not considered the most subtle of media, I am nonetheless struck by the level of detail in some of the designs. For example, the thoughtful placement of differently colored tesserae grants a simple sack the contrasting light and shadow of folds and creases.

And a visit to the new galleries is also a multi-sensory experience, for better or for worse. In addition to the tantalizing visual treats and pleasant touch of sunshine on one’s skin, the cacophonous ringing of overambitious alarms when one so much as graces some works of art with too discerning a glance can be a bit distracting. Thankfully, in the weeks since the galleries’ debut, it seems that many sensors have been re-tuned to be a little more forgiving.

For a far more rewarding audial experience, however, head to the back corner of the Roman collection, where you’ll find a little conservation nook with pieces that recently underwent restoration and an interesting video surveying the history of the collection and conservation techniques.

Another multimedia feature you’ll find dispersed throughout the new galleries is an interactive educational resource called LaunchPad installed on 16 Apple iPads. LaunchPad goes beyond the gallery labels, offering up a wealth of information for selected objects including historical context, form and function, method of manufacture, and connections with other works in the museum’s collection. You could easily spend an hour or two absorbed in LaunchPad alone.

Also on loan for an initial nine-month period are 51 stunning works from the British Museum organized in a special exhibition called Late Roman and Early Byzantine Treasures from the British Museum. As far as things go in the museum world, that’s a pretty lengthy period for a temporary exhibition. We can be thankful that the British Museum is remodeling their Byzantine galleries, which permits American audiences to become enriched by these treasures across the pond over in “The Colonies.” One of the highlights of the British Museum loan is the Lycurgus Cup, a fascinating 4th century Roman luxury object. Made of dichroic glass, meaning “two colors,” the cup changes from red, when light shines through the glass, to green, when reflecting off the surface. A clever lighting rig in the ceiling permits you to see this magical transformation before your very eyes.

Late Roman and Early Byzantine Treasures from the British Museum is on display at the Art Institute through August 2013. Be sure to catch it while it’s there, as it’ll likely be a long time before these exquisite treasury objects leave London again. But after the British Museum loan leaves, that space in the Art Institute will serve as a venue for rotating special exhibitions of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine art. So, with over 550 works in the new permanent Jaharis Galleries of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Art, and the special exhibitions, we can look forward to plenty of new fodder for this epic adventure of the Ancient Art Podcast.

Thanks for tuning in. Don’t forget to “like” us on Facebook and follow me on Twitter. Subscribe to the podcast on iTunes, YouTube, and Vimeo, and be sure to give us a rating and leave you comments. You can also reach me at info@ancientartpodcast.org or use the online form at http://feedback.ancientartpodcast.org. Happy hunting and we’ll see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2013 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[2] See especially episode 5 on A Corinthian Pyxis, our three-part series on the Parthenon Frieze, and episodes 15 and 16 on the Origin of Greek Sculpture and the Metropolitan Kouros.

[3] See episode 13: Ellsworth Kelly’s “Chicago Panels”.

[4] See episode 7: Gandharan Bodhisattva.

[5] Personal correspondence with Art Institute conservator Emily Heye, 20 November 2012.

[6] You’ll find Joan Miro’s statue referred to as Moon, Sun, and One Star (Miss Chicago), and Miro’s Chicago.

———————————————————

See the Photo Gallery for detailed photo credits.

Media courtesy of:

Apple Garageband

Art Institute of Chicago

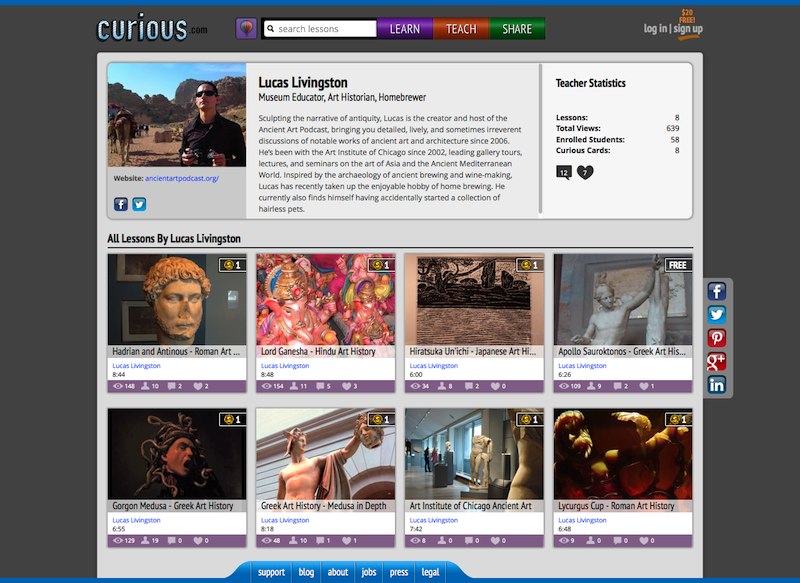

Hi World. I’m excited to make a quick announcement. The Ancient Art Podcast and Curious.com have teamed up to host episodes of the podcast at Curious.com. If you head on over to

Hi World. I’m excited to make a quick announcement. The Ancient Art Podcast and Curious.com have teamed up to host episodes of the podcast at Curious.com. If you head on over to